Spinning plates: balancing pressures for nutrition and planet

Paula Hunt, Nutritionist/Dietitian, project managed the UK Government’s first ever pictorial national food guide in 1994. Thirty years on she reflects on how the guide has been modified since and makes a plea for further modernisation of the Eatwell Guide to incorporate sustainability as well as health considerations. Dismissing fears of ‘nanny state’ Paula believes that the new UK Government has an absolute responsibility to intervene as the consequences of the nation’s eating habits place a huge burden on the NHS as well as the state of our planet.

Paula sets out the recent evidence to support change and discusses the challenging and contentious areas for an improved British diet that will help meet our net zero 2050 target. She believes there is a compelling need to update the Eatwell Guide and that its application should not only be for public information but also as a reference diet for the whole food supply system. Without changes in legislation and taxation for food producers however, she fears the nation’s food consumption will continue to be driven primarily by the food and hospitality industries who will always place profits above public health or protection of the planet.

Origins and evolution of The Eatwell Guide

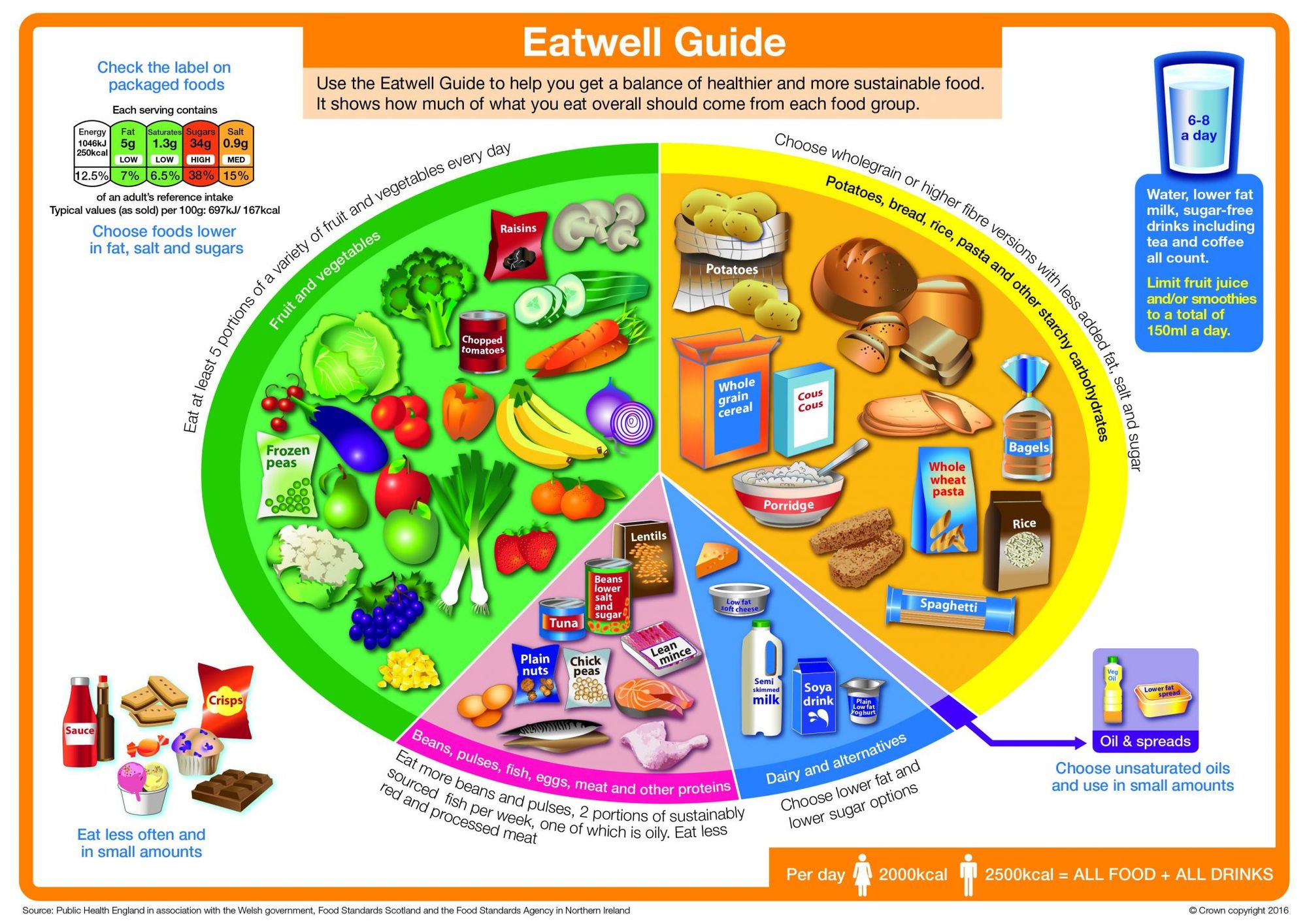

The Eatwell Guide defines the Government’s current advice on healthy eating and is a visual representation of how different foods contribute towards a healthy balanced diet. [1] Used as an educational tool for public messaging it is the nearest we presently have to a ‘reference diet’ for the nation. [2] It was last updated in 2016, but its origins go back thirty years.

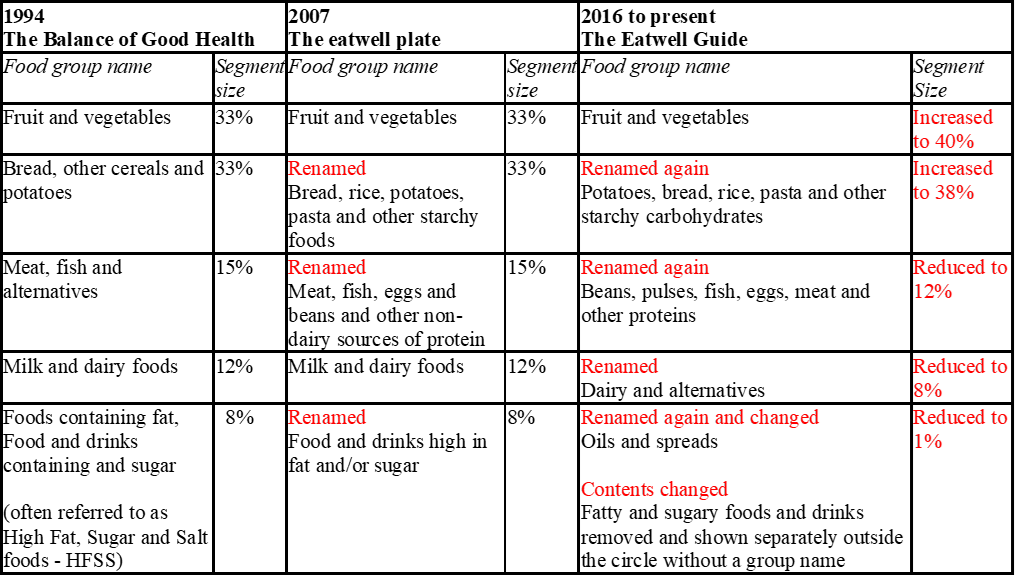

Its predecessor, and the first nationally recognised food guide in the UK ‘The Balance of Good Health: The National Food Guide’ was launched in 1994. Looking rather dated now, at the time its purpose was to provide consumers with practical and realistic guidance for selecting a healthy diet thereby reducing the potential for misinformation and misunderstanding.[3] It was very much about individuals and education and was the responsibility of the Department of Health who worked in collaboration with the then Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and the Health Education Authority.

In 1994 health was the sole focus, in particular concerns about rising obesity levels. It was feared that, on the trajectory at that time, adult obesity prevalence might reach as high as 6-8% by 2005. [4] Staggeringly, recent data show that now, 26% of adults are obese and a further 38% of adults are overweight. [5] With a shocking 64% of over-18s in England now carrying excess weight clearly the biggest influence on health has been the food producers with their overproduction of highly calorific, heavily advertised, cheap and easily accessible foods with relatively little nutritional value. The Balance of Good Health – a mere information tool – was a drop in the ocean with almost zero chance of empowering the public to demand and consume a healthier diet amidst the backdrop of an increasingly noxious food supply.

The original ‘plate’ had five food groups and portrayed carefully selected foods, using non-branded images.[6] Objective nutritional criteria were used to calculate the food group segment sizes, using current eating patterns as the starting point, not only to ensure scientific robustness but to allay any possible resistance, particularly from the food industry.[7] The tilted plate graphic, with a knife and fork was to encourage sit-down meals rather than the emerging trend of ‘eating on the hoof’ often involving heavily processed foods high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) such as fast foods, takeaways and snacks.

Unsurprisingly, the main challenge in the development of The Balance of Good Health was addressing objections from key players in the food system – particularly those in the meat, dairy and HFSS sectors – who fought for a more prominent bite of the proverbial cherry. Their lobbying efforts were intimidating and their influence in Government circles alarming. Some segment sizes were slightly enlarged, and pictures of some food items placed in a more prominent position; the food industry is not known for its concern over human health.

A minor revision in 2007, by the Food Standards Agency which had then become responsible for food and health, resulted in it being renamed ‘the eatwell plate’ along with slight name changes to three of the food groups.[8] Otherwise, it was considered still accurate and meaningful.

By 2016 Public Health England – its next new owner – overhauled the eatwell plate. It was renamed The Eatwell Guide, and four of the five food group names were changed as well as the percentage segment sizes of all five food groups. The ‘protein’ and ‘dairy’ groups were allocated slightly less space while ‘fruit and veg’ and ‘starchy foods’ increased a little. The ‘HFSS’ group saw the biggest transformation with these processed foods being declared non-essential so placed outside the main Eatwell Guide circle. That HFSS foods now had no group name or label just simple guidance to ‘eat these foods less often and in small amounts’ was hugely significant and a clear demotion which may have pricked the conscience of the food industry. Nowadays many of these products would be defined as ultra-processed foods (UPF) for which there is huge concern in public health circles and unsurprising trepidation amongst food producers who seem to have fewer hiding places now the science is exposing the true damage caused by such foods.[9]

The removal of the knife and fork reflected that the proportions shown in the guide were not necessarily to be eaten at one meal but more over the course of a day or week as well as that many healthier meals require only a fork (stir fries, curries, salad bowls), a spoon (soups) or no cutlery at all (sandwiches, wraps).

Comparisons of food group names and segment sizes in the UK Government’s national food guides

A future where both health and environment matter

Incorporating environmental considerations had not been on the agenda until the 2016 Eatwell Guide claimed to help you get a balance of healthy and more sustainable food. That reference to sustainability was a nod to the Government’s work towards achieving the United Nation’s globally agreed 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015.[10] In truth, Public Health England commissioned a small post-hoc sustainability assessment of the modelled scenario which did not inform decisions around the format of the Eatwell Guide but simply indicated it had a lower environmental impact than the current UK diet.[11]

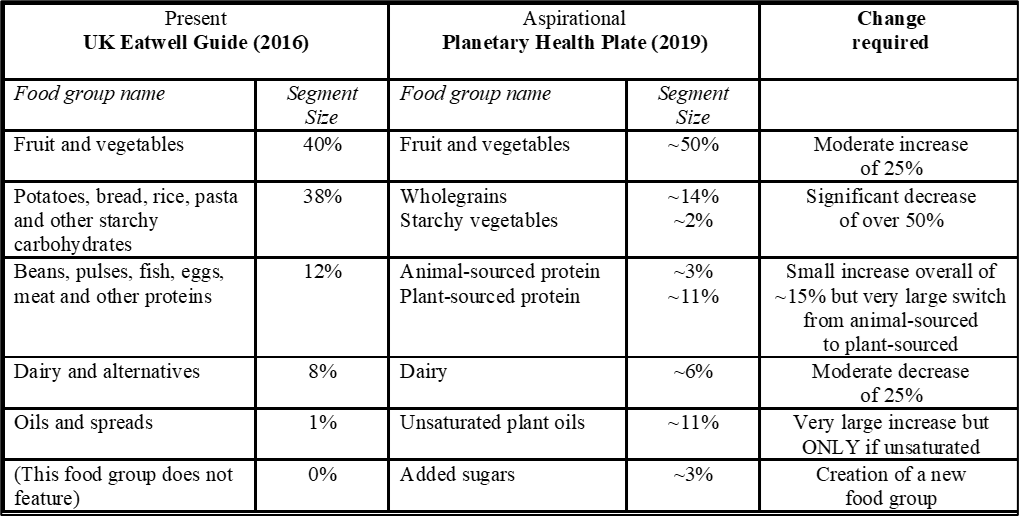

With the UK signed up to net zero by 2050, significant changes to the national diet are now needed to meet the Government’s health, climate and nature commitments.[12][13] Indeed, work in 2021 on plans for a National Food Strategy[14], commissioned by the Government but shelved post-publication, called for concrete proposals to achieve a 30% increase in fruit and vegetable consumption, a 50% increase in dietary fibre, a 30% reduction in meat and 25% reduction in the consumption of HFSS foods. Certainly, dietary guidelines in developed countries globally are consistent in the call for more vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat dairy (or alternatives), and legumes and lessred and processed meats, sugar-sweetened drinks, sugary foods, and refined grains.

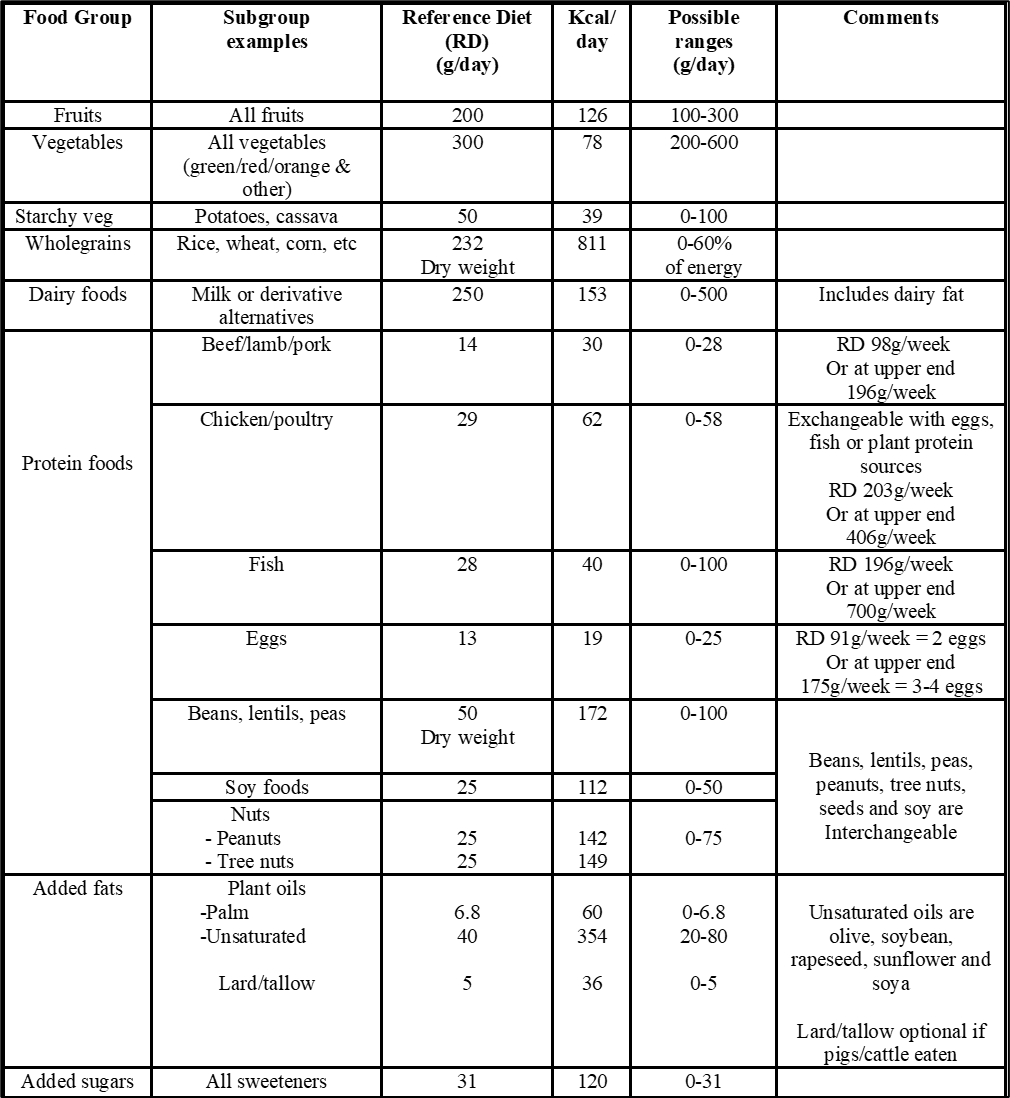

For more quantified food guidance the ranges produced by a group of academic experts ‘EAT-Lancet’ in 2019 are a key benchmark. The researchers combined nutrition and environmental considerations to produce a population-based global healthy and sustainable reference diet.[15] The wide range given for foods and food groups is shown in Appendix A and these figures provide a framework on which country-specific food based dietary guidance can be built, taking account of the nation’s typical eating patterns and being mindful of local food supply/availability. Three food categories – fruits, vegetables and unsaturated oils – are essential for everyone globally, but the place for many other foods is interchangeable and will vary enormously depending on country availability and – down the line – personal preferences.

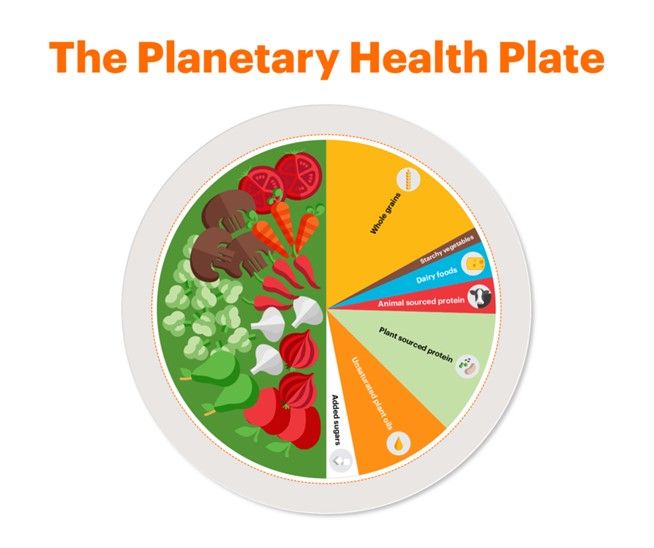

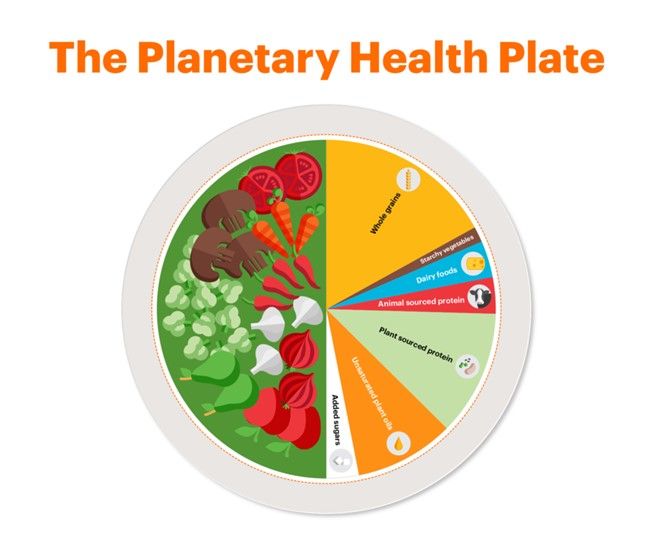

The EAT-Lancet 2019 team’s interpretation of its theoretical modelling into a pictorial guide helps make more practical sense of the figures in Appendix A. They declare that nothing less than a major food transformation is required, moving towards a flexitarian diet, largely plant-based but optionally including modest amounts of fish, meat and dairy foods. Its ‘Planetary Health Plate’has eight food groups in significantly different proportions to the 2016 Eatwell Guide. It has a larger fruit and vegetable segment of 50%, a tiny separate ‘starchy vegetables’ segment (~2%), a modest wholegrains segment of just ~16%, a small dairy foods segment of ~6% and an even smaller animal sourced protein group of ~5%, but a substantial separate plant sourced protein group of ~11%, unsaturated plant oils are about 7% and an added sugars group takes about 3% of the circle.[16]

Using the EAT-Lancet work as an impetus, a small number of nations have recently incorporated environmental concerns within their food for health messaging. The Nordic Nutrition Recommendations (2023) now have a nutrition and dietary framework upon which healthy and sustainable food guidance can be built and invites each of its eight member countries to define its own national environment-friendly, food guide.[17]

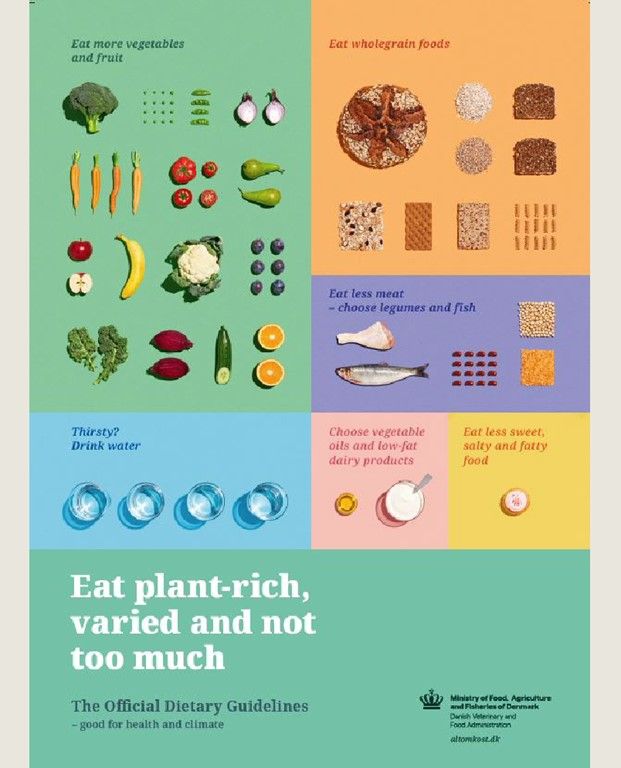

Launched in 2022, Denmark’s ‘Official Dietary Guidelines - good for health and climate’ state their commitment to environmental concerns explicitly in the title and the strapline ‘Eat plant-rich, varied and not too much’ has three simple yet meaningful messages.[18] The nation’s visual food guide shown below is rectangular in shape rather than a circle or sphere and interestingly no red meat or eggs are depicted at all although chicken and fish are displayed.

The German Nutrition Society (DGE) recently launched its Nutrition Circle which splits proteins into two separate groups – one for animal-sources and the other plant-sources of protein called ‘legumes and nuts’.[19] This highlights the extremely small target quantities of meat, poultry, fish or eggs for the implementation of a healthy and sustainable diet without necessarily becoming vegetarian or vegan.

Contentious issues

Nutrition is a relatively young science with new evidence continually emerging. That the science is not yet complete is a lame argument for those who prefer to do nothing – not least the food industry. Fortunately,there is robust evidence that dietary patterns with low environmental impacts can also be consistent with good health – a win-win is possible – and action is needed now, not later.[20]

The two main contradictions are poultry and fish – both of which are obvious alternatives to red/processed meat on health grounds but can be much less beneficial for the planet unless sustainably sourced. Certainly, the biggest area for debate in the UK is in relation to the ‘protein’ group; as a traditionally meat-eating nation, the challenge to consume less red meat and meat products is considerable.

On health grounds, recommendations to reduce red meat (beef, lamb, pork) and processed meat (ham, bacon and sausages etc.) from an average of 90g to 70g per day – or 350g cooked meats maximum per week – have been in place since 2015 because of their link with colorectal cancer.[21] Chicken consumption has increased massively as a result, but such high consumption is undesirable on environmental grounds, although not health unless it is highly processed or deep fried. The large amounts of grain required for mass production of poultry is unsustainable as grain has other valuable uses. Neither is there sufficient ‘food waste’ to provide for such a large-scale poultry industry. So instead of poultry, red and processed meat should be swapped with plant-based protein sources such as beans, pulses, legumes and nuts.[22] Livestock is by far the biggest contributor to dietary greenhouse gas emissions, but recent consumer research showed that although the public has a reasonable tolerance for state intervention, 75% were not supportive of the notion of a tax on fresh meat.[23] Reducing our reliance on animal-based protein in line with the EAT-Lancet reference diet amounts of 14g/day (98g/week) of red meat and 29g/day (203g/week) of poultry would probably mean avoiding meat and poultry four days each week. The guidance to have several meat-free days a week is feasible for some people but a non-starter for many as, despite much more diversity in the British diet in recent decades, eating meat is ingrained in the traditional British way of eating.

Eating fish is an obvious alternative to meat and the UK Government’s present health advice is to eat fish at least twice a week (2 x 140g so 280g total), at least one portion of which should be oily fish, like salmon, sardines or mackerel. However, eating more fish is not straightforward as the oceans couldn’t sustain this level of consumption if the entire British population followed the government guidelines.[24] EAT-Lancet shows a range for fish consumption globally of 0-100g per day and a reference diet amount of 28g a day (196g a week) – so significantly less than the 280g a week currently recommended in the UK. In nations which have ample fish supplies, an upper amount of 100g a day (700g a week) of fish is acceptable but a reduction in the amount of fish currently recommended in the UK is needed on sustainability grounds. As EAT-Lancet shows fish to be interchangeable with poultry, eggs or plant-sources of protein, an approach based on assessment of the realistic supply of sustainably caught fish available in Britain is required. Estimates based on UK landing data seem to suggest that a recommendation of just 100g of fish a week – that’s half the amount presently recommended - is more responsible.[25]

Eggs are also a hard one to crack. Now that previous concerns about eggs causing increased blood cholesterol levels have been allayed, other than being ‘an alternative protein source to beans, pulses, meat and fish’ there is currently no explicit UK Government advice about how many eggs is reasonable. The EAT-Lancet’s reference diet includes 13g eggs a day (range of 0-25g), so barely 2 eggs a week (91g) or at the higher end of the range, 175g which is closer to 3 or 4 eggs weekly. The unsustainability of poultry production for meat on a mass-scale described above means that ‘back-yard hens’ for eggs and eating the poultry meat only from ex-laying stock is the optimal scenario on sustainability grounds. Eggs have the lowest carbon emissions amongst animal protein foods and are an excellent source of protein and iron as well as being low in total fat. As a versatile and accessible food in the UK, eggs have a secure place for people switching to flexitarian, pescatarian, or vegetarian (but not vegan) diets.

Second to meat, dairy foods are perhaps the next biggest tradition in the British diet and trends data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey shows that dairy consumption remains high, despite the recent emergence of plant-based non-dairy alternatives. However, milk, cheese and butter (placed in the fats food group) are major contributors to carbon emissions. EAT-Lancet’s reference diet states 250g/day of milk and cheese (or derivative equivalents) and although the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations suggest 350-500ml of milk and dairy a day, the Germans have interpreted the science to mean just two servings daily. The current UK guidance does not quantify dietary goals for dairy, simply suggesting people choose lower fat and lower sugar options and when buying dairy alternatives to go for unsweetened, calcium-fortified versions.

So, should we all aim to become vegans? Not necessarily. Although vegetarian and vegan diets have a lower environmental impact than the typical UK diet, sustainable diets do not have to be vegetarian or vegan. Indeed, expert consensus is that pushing a vegan message may well be counterproductive.[26] Language can influence and motivate dietary change, and research has shown that linking more sustainable or plant-based eating to vegetarianism or veganism significantly lowers the likelihood of most people changing their eating behaviour. The current appetite for meat is unsustainable however so more people eating more protein-rich plant-based alternatives to meat, more often will certainly help. Examples include soy (tofu, tempeh, edamame beans), mycoprotein (eg. Quorn), beans (chickpeas, black beans, butter beans, kidney beans) and legumes (e.g. lentils, peas, peanuts, peanut butter). Artificially produced non-meat foods in the form of patties/burgers, mince or nuggets were initially created for vegans/vegetarians and considered healthy. Seeing an opportunity for growth, they have more recently been pushed by the marketeers as a plant-based option for ‘meat-reducers’ but they are almost always ultra-processed so not necessarily a good solution. Choosing more natural plant-based foods is better

or, if such products exist, seeking out processed plant-based items which contain 5 or less ingredients, all of which you would find in your own kitchen.

Conclusion

The urgent need for Government action to review the Eatwell Guide is clear and there is little controversy about what change is needed to promote a healthy and sustainable diet. Even food companies agree they want to do things better but say changes will require legislation to ensure a level playing field.

EAT-Lancet’s Planetary Health Plate could form the basis of an updated UK Eatwell Guide fit for the future and approximate differences in the food group sizes are shown below:

Additional messaging such as ‘opt for seasonal, locally sourced fruit and vegetables, avoiding air freight, and plastic packaging’ and ‘avoid food waste where possible’ will be needed along with advice to aim for several meat-free days a week. Reassurance that there is still a place for a small amount of meat, meat products and poultry is important but a reduction in the amounts of fish recommended weekly is needed. The concept of ‘flexitarianism’ should be promoted.

In practical terms, educational materials such as the excellent British Dietetic Association’s ‘One Blue Dot’ materials on ‘An environmentally sustainable diet’ will be vital to update and inspire those involved in educating the public about a healthy and environmentally friendly diet.[27] Education in schools, cookery lessons for all age-groups and community initiatives such as community gardens and vegetable patches will also be important to inspire and upskill people in cooking from scratch and plant-based eating. A sister ‘What we eat now Guide’ depicting the typical British diet currently consumed alongside the proportions being aimed for in the Eatwell Guide would be a useful visual aid to help the public better understand the dietary changes required.

The introduction of targets for both ‘sustainable food’ and ‘diet-related health’ should be an urgent priority for the new Government. But the onus should not just be on citizens to make better choices. An updated Eatwell Guide which incorporates health and sustainability should form the nation’s reference diet to be used across the whole food system. Such targets will show the change required but achieving this is only going to be possible through regulation of the food industry. Forcing the hand of businesses to serve up something considerably better must be a key priority for the new government.

Related Work:

Appendix A

A healthy ‘Reference Diet’ (RD), with ranges, for an intake of 2500 Kcal/day.

[1] Published 2016 by Public Health England (now Office for Health Improvement and Disparities) The Eatwell Guide

[2] Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2024) The Eatwell Guide: how to use in promotional material

[3] Hunt, P., Rayner, M. and Gatenby, S. (1995) ‘A national food guide for the UK? Background and development’. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics8(5) pp. 315-322. Available at: doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.1995.tb00325.x

[4] Department of Health (1992) The health of the nation: a strategy for health in England

[5] NHS England Digital (2022) Health Survey for England, 2022 Part 1

[6] Hunt, P. Gatenby, S. and Rayner, M. (1995). ‘The format of the National Food Guide: performance and preference studies’. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 8(5) pp.335-351. Available at: doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.1995.tb00327.x

[7] Gatenby, S. Hunt, P. and Rayner, M. (1995) ‘The National Food Guide: the development of dietetic criteria and nutritional characteristics.’ Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 8(5) pp.323-334. Available at: doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.1995.tb00326.x

[8] Food Standards Agency (2007) The eatwell plate. See Eatwell from Plate to Guide, for history and evolution.

[9] Monteiro, C. A. et al. (2019) ‘Ultra-processed Foods: What they are and how to identify them’ Public Health Nutrition 22(5) pp. 936-941. Available at: doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003762

[10] Department for International Development (2019) UK’s Voluntary National Review of the Sustainable Development Goals

[11] Carbon Trust (2016) The eatwell guide: A more sustainable diet. Understanding the environmental impact of Public Health England's updated Eatwell Guide nutritional guidance

[12] Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (2023) Net zero government emissions: UK roadmap DEFRA (2023)

[13] See Environmental Improvement Plan 2023, DEFRA

[14] Dimbleby, H. for DEFRA (2021) The National Food Strategy

[15] Willett, W. et al. (2019) ‘Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems.’ The Lancet. 393(10170), pp. 447-492 Available at: doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31788-4

[16] The Planetary Health Diet

[17] Nordic Co-operation (2023) Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023

[18] Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (2021) The Official Dietary Guidelines – good for health and climate

[19] German Nutrition Society (2024) DGE Nutrition Circle

[20] ‘Fischer, C.G. and Garnett, T. (2016) ‘Plates, pyramids, planet. Developments in national healthy and sustainable dietary guidelines: a state of play assessment.’ Available at: FAO.

[21] World Cancer Research Fund International (2015. Meat, fish, dairy and cancer risk)

[22] See reference 14.

[23] Food Farming and Countryside Commission (2024) The Food Conversation

[24] Ellis, M. and Clarke, F. (2024) ‘What are the best (and worst) types of fish to eat for health?’ Fish For Health: 7 Best To Eat and What To Avoid (zoe.com). In this article, the authors cite Professor Tim Spector: “if the entire population were to follow the government guidelines, the oceans wouldn’t be able to sustain it”.

[25] Based on landing and loss estimates by Firkins, T. (2024) shared in personal communication

[26] Wise, J., Bacon, L. and Vennard, D. (2018) ‘How language can advance sustainable diets. A summary of expert perspectives into how research into the language of plant-based food can change consumption.’ Language.

[27] British Dietetic Association: The Association of UK Dietitians (2020) One Blue Dot - the BDA's Environmentally Sustainable Diet Project

Ultra Processed People

Peter Sims reviews Chris van Tulleken book 'Ultra Processed People' published 2023. He concludes with nine fundamental lessons, which apply much more widely than the food sector. The books follows the money, cuts through the controversy and there will be something in it that surprises everyone.

Ravenous

George Ttoouli reviews Henry Dimbleby's 'Ravenous', finding it to be solidly-informed but insufficiently bold in its vision.

Spinning plates: balancing pressures for nutrition and planet

How should the UK's Eatwell Guide be brought up to date, incorporating sustainability as well as health considerations?

Building Community Food Webs

Anne Chapman review 'Building Community Food Webs' by Ken Meter (Island Press , 2021).

A Just Transition in Agriculture Podcasts

A Just Transition in Agriculture podcasts - four part series

A Small Farm Future

Chris Smaje argues that the best future we can now hope for is a small farm future (as opposed to the increasingly big farm present), in which many more people than now are involved in food production, mostly on privately-owned small-holdings – realising the old demand for ‘three acres and a cow’.

The Future of Farming

“Rather than fixating on veganism as being the answer to reducing the impacts of our food system we need to have a better understanding of the complexities of farming.” Director of Green House think tank Anne Chapman suggests an alternative way of looking at reducing carbon emissions from farming.

Food in a Changing Climate

Food in a Changing Climate is part of a series called SocietyNow. Books in this series are intended to be ‘short, informed books, explaining why our world is the way it is, now’ and that make ‘the best of academic expertise accessible to wider audience’

English Pastoral: An Inheritance

James Rebank's book is a personally written memoir, examining Nostalgia, focussed on how his grandfather farmed; Progress, the attempts Rebanks and his father made to try to ‘keep up’ with modernising farms; and Utopia, about how he is trying to farm now and pass on knowledge to his children

Regenerative Agriculture - George Hosier, Wexcombe Manor Farm

An interview with George Hosier of Wexcombe Manor Farm in Wiltshire about the changes he has made to his farming practices to improve soil fertility, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase biodiversity while reducing his costs.

Farming for Nature - Bill and Cath Grayson, Morecambe Bay Conservation Grazing Company

An interview with Cath and Bill Grayson who run Morecambe Bay Conservation Grazing Company in North West England about how they came to do conservation grazing, what makes it different from how beef and lamb are normally produced and its benefits for wildlife.

A Just Transition in Agriculture

The agriculture industry has transformed in the last 70 years. Agriculture needs a just transition as much as coal mining communities do, but whereas there is no future for coal mines in a zero-carbon world, there has to be a future for agriculture.

Bringing Back the Beaver, the story of one man's quest to rewild Britain's waterways.

Of all the animals that roamed these isles but have now disappeared many think that the beaver is the most important one to bring back. Like us, beavers are ecosystem engineers, modifying their habitats to suit themselves

Dirt to Soil: one family's journey into Regenerative Agriculture

Gabe Brown discusses his principles of soil health and is useful to farmers and anyone concerned with food production and the state of farming.

Wilding; the Return of Nature to a British Farm

Wilding raises two key issues. One is the challenge it poses to the established UK approach to nature conservation, and our approach to nature more generally. The other is whether we have more than enough food and should instead of producing food give land, such as that at Knepp over to Nature.